Inside the Largest Beyond Visual Range (BVR) Aerial Combat between India and Pakistan

May 14, 2025

By Fazal Gilani and Syed Bahadur Abbas

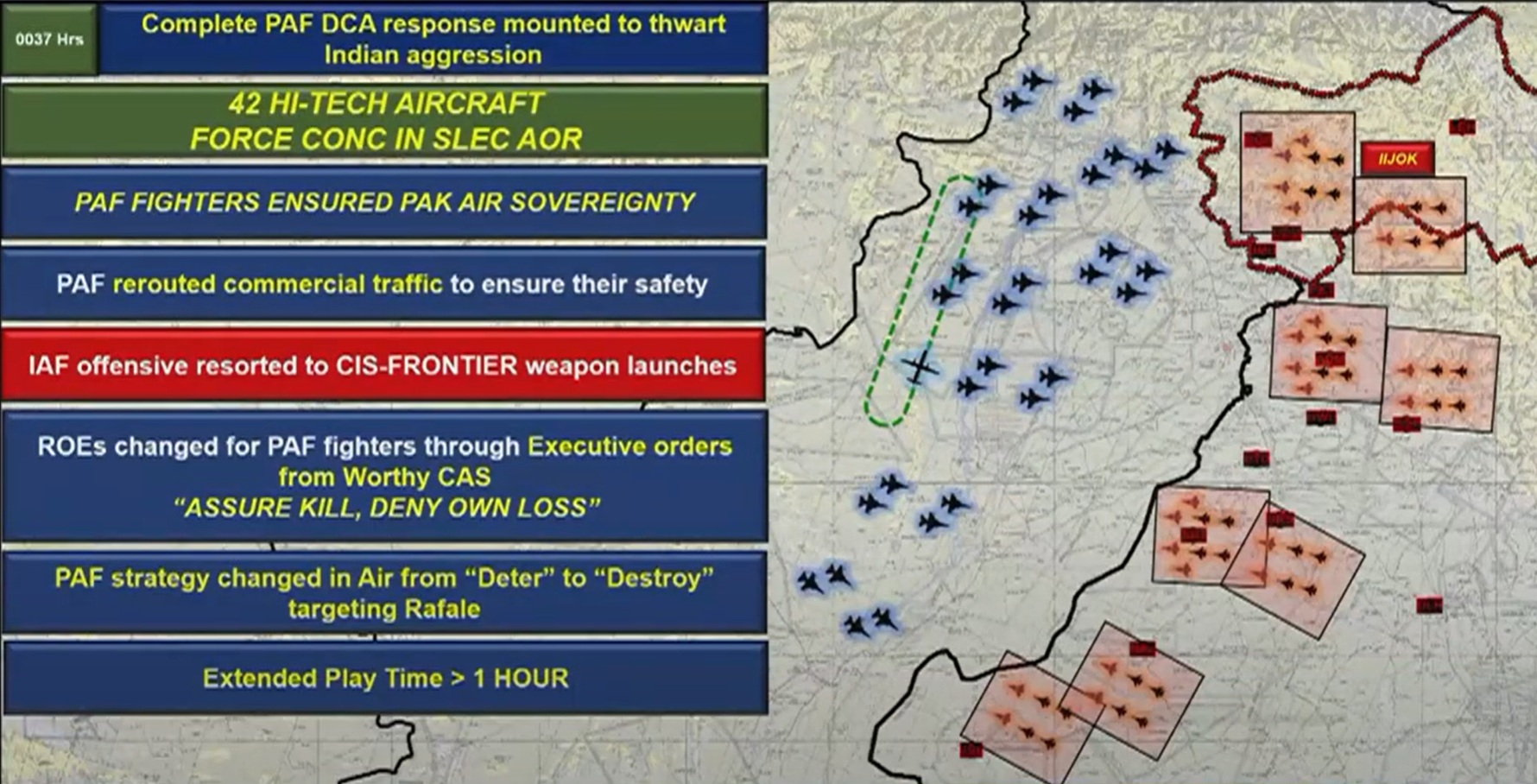

In a detailed public briefing on May 10, 2025, Pakistan Air Force (PAF) Director General Public Relations Air Vice Marshal Aurangzeb Ahmad disclosed critical insights into what officials are calling one of the largest aerial engagements between India and Pakistan in recent history.

Military analysts describe this aerial combat, characterized by long-range missile duels and high-altitude coordination, as one of the most extensive air battles since World War II, marking a significant milestone in the evolution of Beyond Visual Range (BVR) warfare.

The aerial encounter between the Pakistan Air Force and Indian Air Force (IAF) was not a conventional or cinematic dogfight of barrel rolls and tail chases. Instead, it was a display of cutting-edge BVR combat – a domain where missiles fly hundreds of kilometers, aircraft engage without visual contact, and success is defined by electronic warfare superiority.

The aerial confrontation between the two advanced military powers of South Asia showcased the technical maturity, doctrinal depth, and operational coordination required for a modern-day BVR warfare, which has now reached a new apex of effectiveness, especially in the regional context of India and Pakistan.

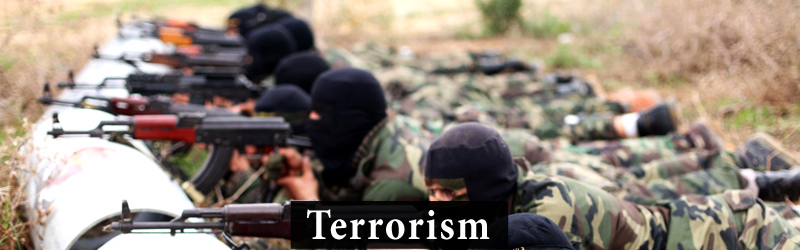

BVR Warfare

BVR air combat refers to engagements where aircraft target and launch missiles at enemy planes without seeing them, typically from ranges beyond 30–50 kilometers, extending up to 300 kilometers depending on the missile and platform.

Historically, BVR warfare dates back to the 1950s with the development of the AIM-7 Sparrow, an early semi-active radar-guided missile. However, Vietnam War-era combat showed that BVR was limited by radar clutter, poor missile reliability, and a lack of pilot training. Despite the existence of the tools and technology, most of the kills during this era were still achieved through conventional within-visual-range (WVR) engagements.

It was not until the 1991 Gulf War that BVR combat truly came of age. U.S. Air Force F-15s, supported by Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) and advanced Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) systems, recorded dozens of kills with AIM-7 and AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAMs), often at ranges exceeding 50 km. The combination of better sensors, datalinks, and robust command-and-control drastically improved kill probability at range.

Today, BVR is the dominant air combat paradigm. While WVR still exists, especially in close-proximity skirmishes or against irregular threats, the decisive edge in any near-peer engagement lies with who can see first, shoot first, and jam best.

Technical Battlefield – BVR's role in India-Pakistan Aerial Confrontation

According to the PAF, the skies during the May 2025 standoff saw the deployment of over 100 aircraft from both sides, around 70 from the IAF and 40 from the PAF. While on paper this may suggest numerical superiority for India, the hour-long aerial battlefield was shaped not by numbers, but by net-centric warfare, a technical ballet involving real-time sensor fusion, missile range envelopes, and electronic countermeasures.

The unique geography of the India-Pakistan border, especially near the Line of Control (LoC), makes BVR engagements especially suited for escalation control.

1. Standoff Postures: The proximity of India and Pakistan’s operational theaters allowed the aircraft to fly within their sovereign airspace while still engaging enemy targets, reducing the diplomatic consequences of cross-border incursions.

2. Sensor Range Advantage: With the flat Punjab plains and high-altitude AWACS coverage, both sides enjoy significant radar horizon advantages, enabling long-range engagements without terrain masking.

Pakistan Air Force briefing on recent India-Pakistan aerial conflict, on May 7, 2025. (Image Credit: PAF/PTV)

Pakistan Air Force briefing on recent India-Pakistan aerial conflict, on May 7, 2025. (Image Credit: PAF/PTV)

3. Short Time-to-Target: In such compact battlespaces, even a missile launched at 150 km can reach its target in under two minutes. That compresses the OODA loop (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act) and emphasizes pre-fight positioning, data superiority, and command responsiveness.

4. Rules of Engagement (ROE) Flexibility: As soon as India launched stand-off munitions from within its own territory, PAF changed the rules of engagement in the air from “deter to assure kill and deny own loss”. This allowed pre-emptive missile launches based on radar lock, rather than waiting for visual confirmation.

According to the PAF, the IAF fighters got airborne in large numbers (around 60 to 70 jets, including 14 Rafales). In response, Pakistan Air Force commenced multi-domain operations by deploying 42 aircraft to deter Indian jets. PAF claims to have shot down 5 Indian jets, including:

• 3 Rafales

• 1 MiG-29

• 1 Su-30MKI

According to the IAF, India targeted some PAF jets; however did not provide further information on which Pakistani jets were locked or targeted. India has confirmed its losses in aerial combat but did not provide detailed information on the involved aircraft. However, Pakistan cites radar logs, bearing data, and missile telemetry to back its claims, suggesting a well-documented sensor-driven kill chain.

Unlike conventional dogfights, these aircraft operated in multi-tiered formations, maintaining distances of 100–150 kilometers horizontally, and using altitude stacks to separate engagement roles, escort, intercept, jammer, and surveillance. These formations reduced the risk of mid-air conflict, deconflicted missile zones, and enabled clearer command hierarchies.

Chinese AVIC PL-15 missile. (Image Credit: Chinese social media)

Chinese AVIC PL-15 missile. (Image Credit: Chinese social media)

BVR Weapons that Defined India-Pakistan Encounter

The clash mainly involved Pakistan Air Force’s JF-17 Thunder and J-10Cs and Indian Air Force’s Rafales, Su-30MKIs, and MiG-29s. Both sides deployed AWACS to coordinate real-time targeting, and long-range air-to-air missiles such as the PL-15 and Meteor.

• PL-15 (China): Equipped on PAF’s J-10C fighters, this advanced active radar-guided missile is believed to have a range of 200–300 kilometers. Its dual-pulse motor and data link allow mid-course updates, making it a formidable “fire-and-adjust” missile that tracks even evasive targets.

• Meteor (Europe): Deployed on India’s Rafale, the Meteor is considered the most advanced Western BVR missile, with a solid ramjet engine allowing it to maintain kinetic energy over long distances. It is designed for no-escape zones, targets that, once locked, cannot evade through maneuvering alone.

The skirmish marked the first operational test of both missile systems against each other, under real combat conditions and active jamming environments.

Sensors, Jammers, and the Data War

The real battle, however, was not between missiles but between sensor networks and electronic warfare systems.

• Pakistan deployed a Defensive Counter-Air (DCA) strategy. This involved using airborne early warning aircraft (such as the ZDK-03 Karakoram Eagle or Saab Erieye) to track India’s formations from over 300 km away.

• India, on its side, relied on Phalcon AWACS and ground-based radars integrated with Rafales and Su-30MKIs.

Rafale fighter jet with METEOR Beyond Visual Range Air-to-Air Missile (BVRAAM) system. (Image Credit: French Ministry of the Armed Forces)

Rafale fighter jet with METEOR Beyond Visual Range Air-to-Air Missile (BVRAAM) system. (Image Credit: French Ministry of the Armed Forces)

In this invisible but high-tech war, both sides employed Electronic Countermeasures (ECM). These included digital radio frequency memory (DRFM) jammers, radar decoys, spoofing, and chaff bursts to deflect missile locks or degrade radar tracking. The ability to jam, spoof, and adapt dictated who could launch first, or force the enemy to break lock and lose missile guidance. One PAF official noted, “It wasn’t just about outranging them, it was about denying their sensors a picture. That’s where the fight was won.”

The Quiet Revolution of Air Warfare

Most fighter engagements last between 20–30 minutes due to fuel constraints. This clash, however, reportedly endured for over an hour, likely due to rotational Combat Air Patrol (CAP) tactics and aerial refueling, underscoring the logistical depth behind the scenes.

What made this BVR battle so compelling was not just the hardware, but the software: doctrines, algorithms, radar settings, ROE interpretation, ECM modulation, and human-machine interaction.

This engagement may not have produced dramatic video footage, but it revealed something far more significant: how modern air forces think, prepare, and adapt under real-world conditions.

The Battle Behind the Horizon

The India-Pakistan aerial conflict marks a critical milestone in the evolution of air power in South Asia. It confirmed that aerial dominance today is defined not by who flies higher or faster, but by who sees first, who processes data faster, and who can deny the enemy’s ability to act.

BVR warfare, once a theoretical domain of Cold War planners, is now the main battleground in real conflicts between regional powers. In this new era, the fighter pilot is no longer just a dogfighter but part of a real-time, sensor-driven, and precision-targeted ecosystem.

Whether or not all the claimed kills are ever officially confirmed, one thing is clear: the era of Beyond Visual Range dominance is no longer coming; it is already here.

Pakistan Air Force J10C fighter jet armed with PL-15 and PL-10 missiles. (Image Credit: PAF/via X)

Pakistan Air Force J10C fighter jet armed with PL-15 and PL-10 missiles. (Image Credit: PAF/via X)

Note: The above opinions are the personal views of individual authors or contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of IRIA.

ALSO READ:

Regions

Issues

China’s Ambitions at Sea and Naval Modernization

China’s Ambitions at Sea and Naval Modernization

India-Pakistan Conflict 2025: Fighter Jets, Missiles, and Drones

India-Pakistan Conflict 2025: Fighter Jets, Missiles, and Drones